Words Have Sex

When you bumble around, take care not to stumble and take a tumble, or you might fumble, your cookie might crumble, and the pieces could end up all in a jumble!

Why do these six words ending in -umble all imply some kind of clumsy failure?

This is common in language. Certain sounds can end up meaning a certain thing. For example, -ump usually means some kind of rounded mass: bump, clump, lump, hump, rump, stump. As, another example, uni- means “one”: unicycle, unicorn, universal.

There are two ways this can happen.

In the case of uni-, the words all share the same etymology.1English got the uni- prefix from Latin, which got it from Proto-Indo-European. All words with uni-, whether “unicellular” or “unisex”, derive from the Proto-Indo-European root *oi-no-, meaning “one”. From that root we also get words like “one”, “lonely”, and “none” through Old English, and “ounce”, “inch”, and “university” through Latin.2

But in the case of -ump, the words do not share an etymology. “Hump” comes from Proto-Indo-European *kemb-, meaning bend or turn. “Rump” comes “from or corresponding to Middle Dutch ‘romp’, German ‘Rumpf’” meaning “trunk, torso.”3 “Bump” and “lump” are both unknown, but don’t seem to be related. These words did not come to sound the same because of a shared ancestry, but because of a shared meaning.

Certain sounds feel a certain way to speakers of a language, so when there’s any ambiguity or variance in how words are pronounced, over time those words can converge to have sounds that match the meanings. Meanings may also be inherent in the sound itself.4 Either way, certain sounds end up having consistent meanings across multiple words.

The study of this is called phonaesthetics, a term likely coined by J. R. R. Tolkein(!) to mean the study of the aesthetics of certain speech sounds. This study is essentially separate from linguistics, and is quasi-scientific in nature. Either way, it’s clear certain sounds carry meanings, such as the word “glitter”, which contains gl-, which in English often relates to light (glare, gleam, glimmer, glisten, glow), and -itter, which relates to irregular repetition (chatter, flutter, shatter).

Not all similar-sounding words share the same ancestry just as not all similar biological species share the same ancestry. For example, many non-crab crustaceans have evolved to have crablike bodies, an effect called “carcinization”, a word deriving from the greek “karkinos” meaning crab (related to the word “cancer”). Even though these myriad crab creatures are not particularly related, they end up developing crablike bodies anyway.

Trees have a similar story. Trees are not related in the same way apes are all related, or lizards are all related. Instead, a bunch of unrelated plants independently evolved woody stems and grew into trees. There’s a similar story with fish, too.

Word roots like uni- are like apes and lizards, whereas sounds like -ump are more like trees, crablike crustaceans, and fish.

So what about the -umble words? Do they share an etymology?

They do not:

- “Bumble” is an imitative word, which is supposed to sound like what it means, kind of like an onomatopoeia. (An unrelated “bumble” eventually came to replace “humble” in the older English word “humblebee”, probably to sound more like “Middle English ‘bombeln’ ‘to boom, buzz’.”)

- “Stumble” likely comes from the Proto-Germanic5 root *stam-, the source of the English word “stammer”.

- “Tumble” is comes from Old English “tumbian”, which has unknown origin, but probably comes from Proto-Germanic, given similar words in other Germanic languages.

- “Fumble” is probably from Old Norse “falma” meaning the same thing, which may also be an imitative word.

- “Crumble” comes from Old English “gecrymman”, meaning breaking into crumbs.

- “Jumble” came later than some of these other words and was probably coined in relation to the existing -umble words.

As you can see, these -umble words are clearly more like crabs and trees than apes and lizards. They grew together from unrelated origins. The -b- in several of these words is a clear example of sounds being inserted into words that don’t match the etymology, just to match other words that have similar meaning. Words don’t have to evolve like asexual species, just cloning and mutating over time. Instead they can have sex, taking parts from each other!

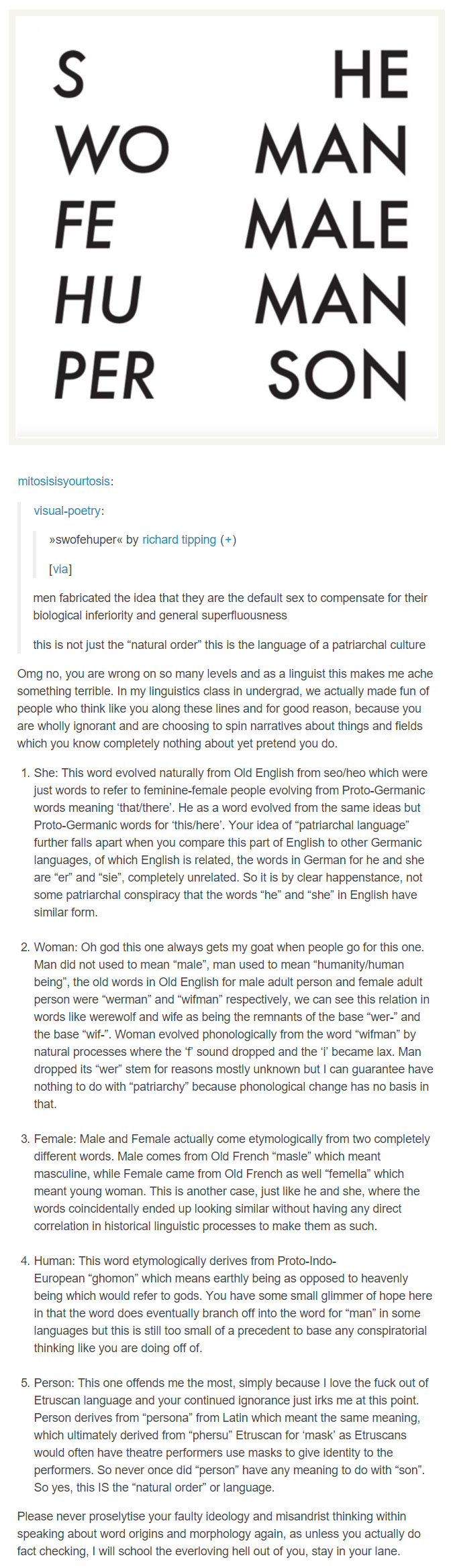

A final warning when it comes to etymologies: If you want to prove two words “aren’t related”, you can’t necessarily just just look up their etymologies, because the words may be related by convergent evolution rather than by ancestry. Otherwise you can end up looking silly, like this person claiming the word “male” and “female” are unrelated simply because they have separate etymologies (same goes for “man”/”woman” and “human”/”man”, but I agree the “she”/”he” and “person”/”son” relations are just silly):

As we’ve learned, two words can be related without sharing an etymology.6 The sounds of words can grow together to match the meanings of the words. So make sure you don’t use etymologies to try to disprove words being related, otherwise you might stumble and take a tumble, and your linguistics knowledge could end up all in a jumble!

Footnotes

-

Etymology is the study of the evolutionary history of words. ↩

-

Words entered English from Latin either directly or through French. Between 30% and 45% of English words come to English through French, though almost all of the most common words in English come from Old English. ↩

-

Thank God for Etymonline, where I look up these etymologies. I was expecting the site to be some massive project sponsored by a university, but it’s apparently compiled by one legend named Douglas R. Harper, pulling information from various texts. Amazing! ↩

-

Proto-Germanic came after Proto-Indo-European, but before Old English, and is the ancestor of all the Germanic languages. ↩

-

“Island” and “isle” would be another example. People say they’re unrelated because they have different etymologies. “Island” comes from Old English “igland”, whereas “isle” comes from Latin “insula”. However, the -s- in “island” clearly comes from association with the word “isle”, making the two words related! ↩